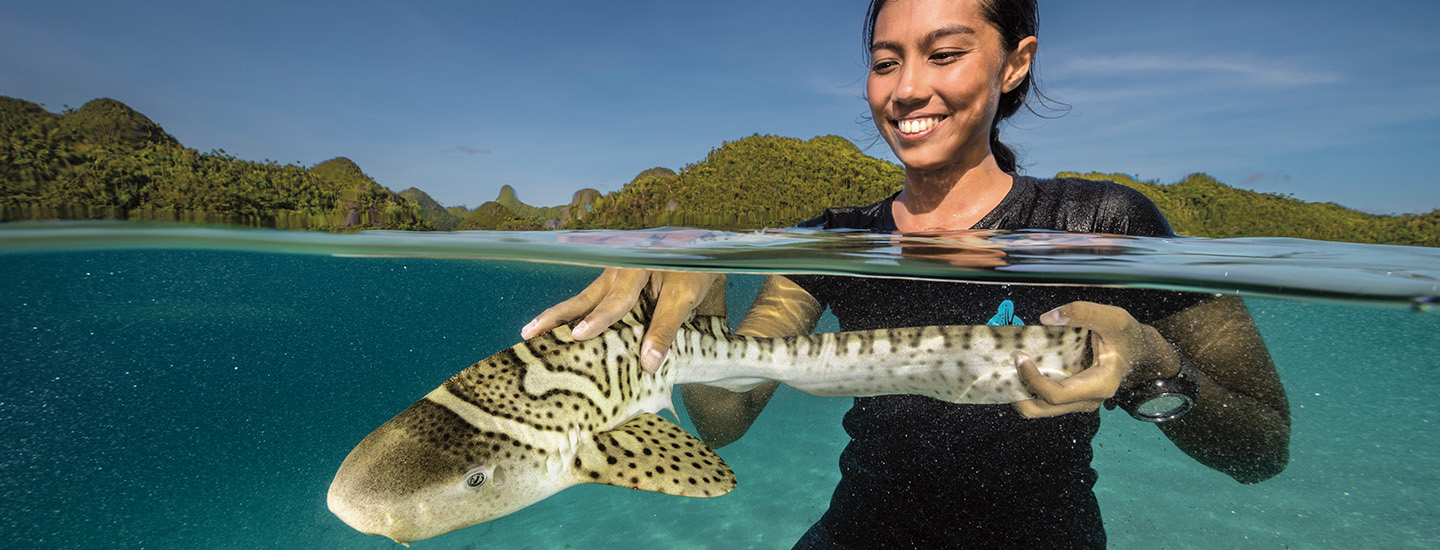

Bubbling water echoes around a biologist at Sea Life Sydney Aquarium in Australia. She leans over a tank to pick up a zebra shark egg. The baby shark growing inside the brown leathery pouch is about to go on an incredible journey. It will travel more than 5,200 miles by car, airplane, and boat from Australia to a remote island in Indonesia (see Going the Distance, below).

Why go to such great lengths for zebra sharks? This endangered species needs all the help it can get. Unfortunately, it isn’t the only one. Of the 1,199 shark and ray species on the planet, more than one-third are threatened with extinction.

In 2019, biologists from around the world gathered to see what they could do to help. They discussed the idea of transporting sharks bred in zoos and aquariums to their native habitats, and the ReShark program was born. Today more than 90 aquariums, conservation groups, and government agencies are part of ReShark.

After years of planning, the first captive-bred sharks were released in January 2023. “It marked an incredible milestone for us,” says Erin Meyer, chief conservation officer at the Seattle Aquarium. “We’re now ready to scale up!”

The sound of bubbling water fills an aquarium in Australia. A biologist leans over a tank to pick up a zebra shark egg. There’s a baby shark growing inside the brown leathery pouch. And it’s about to go on an incredible journey. It will travel more than 5,200 miles by car, airplane, and boat. It will travel from Australia to a remote island in Indonesia (see Going the Distance, below).

Why send a shark so far? Zebra sharks are an endangered species. They need all the help they can get. Unfortunately, they aren’t the only ones. There are 1,199 shark and ray species on Earth. More than one-third are threatened with extinction.

In 2019, biologists from around the world decided to help. They planned to breed sharks in zoos and aquariums, then transport them to their natural habitats. They called the program ReShark. Today, more than 90 organizations are involved.

Starting the program took years of planning. In January 2023, the first sharks bred in captivity were released. “It marked an incredible milestone for us,” says Erin Meyer. She’s the chief conservation officer at the Seattle Aquarium. “We’re now ready to scale up!” she adds.